3724 n. Parker Ave Indianapolis, Indiana 46218

The Panther legacy & Inspiration

The Black Panther Party, an African American revolutionary organization, established in 1966 in Oakland, California, by Huey P. Newton alongside Bobby Seale. The party’s initial aim was to patrol African American communities to safeguard it's citizens against instances of police violence. The Panthers gradually evolved into a Marxist revolutionary faction advocating for the armament of all African Americans, exemption from military drafts for African Americans, and immunity from all punitive measures of so-called white America, along with the liberation of all African Americans incarcerated and the provision of reparations to African Americans for centuries of oppression inflicted by white Americans. At its height in the late 1960s, Panther membership surpassed 2,000, and the organization maintained chapters in numerous significant American urban centers. In the aftermath of the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, that Merritt Junior College students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale established the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense on October 15, 1966, in West Oakland (officially referred to as “Western Oakland,” a sector of Oakland city), California. Shortening its title to the Black Panther Party, the organization promptly aimed to distinguish itself from African American cultural nationalist movements, including the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Nation of Islam, to which it was frequently compared. Despite sharing certain philosophical viewpoints and tactical elements, the Black Panther Party and cultural nationalists diverged on several fundamental aspects. For example, while African American cultural nationalists typically viewed all white individuals as oppressors, the Black Panther Party made a distinction between racist and nonracist whites and formed alliances with progressive members of the latter category.

Additionally, while cultural nationalists predominantly regarded all African Americans as victims of oppression, the Black Panther Party maintained that African American capitalists and elites had the capacity and often did exploit and oppress others, especially the African American working class. Perhaps most crucially, whereas cultural nationalists focused significantly on symbolic systems, including language and imagery, as the means to free African Americans, the Black Panther Party asserted that these systems, while important, are ineffective in achieving liberation. It deemed symbols as grossly insufficient to alleviate the unjust material conditions, like unemployment, generated by capitalism. From the very beginning, the Black Panther Party articulated a Ten Point Program, resembling those of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Nation of Islam, to launch national African American community survival initiatives and to build alliances with progressive white radicals and other organizations composed of people of color. Several positions outlined in the Ten Point Program emphasize a fundamental stance of the Black Panther Party: economic exploitation is at the core of all oppression in the United States and beyond, and the termination of capitalism is a prerequisite for social justice. During the 1960s, this socialist economic perspective, shaped by a Marxist political ideology, resonated with a variety of other social movements in the United States and across various parts of the globe. Consequently, even as the Black Panther Party discovered allies both within and outside the confines of North America, the organization also found itself directly in the sights of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and its counterintelligence initiative, COINTELPRO. Indeed, in 1969, FBI director J. Edger Hoover declared the group a communist organization and an enemy of the U.S. government.

Like Malcolm X, the Black Panthers believed that nonviolent protests could not truly liberate black Americans or give them power over their own lives. They linked the African American liberation movement with liberation movements in Africa and Southeast Asia.

the Black Panther Party evolved from a local organization rooted in Oakland into a global movement encompassing chapters across 48 states in North America and allied support groups in countries such as Japan, China, France, England, Germany, Sweden, Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Uruguay, and beyond.

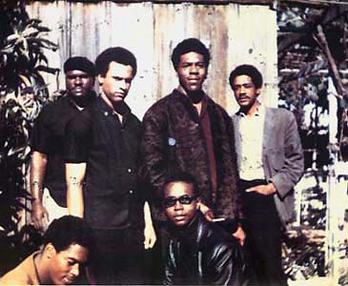

Original six members of the Black Panther Party (1966): Top left to right: Elbert "Big Man" Howard, Huey P. Newton (Defense Minister), Sherwin Forte, Bobby Seale (Chairman);Bottom: Reggie Forte and Little Bobby Hutton (Treasurer).

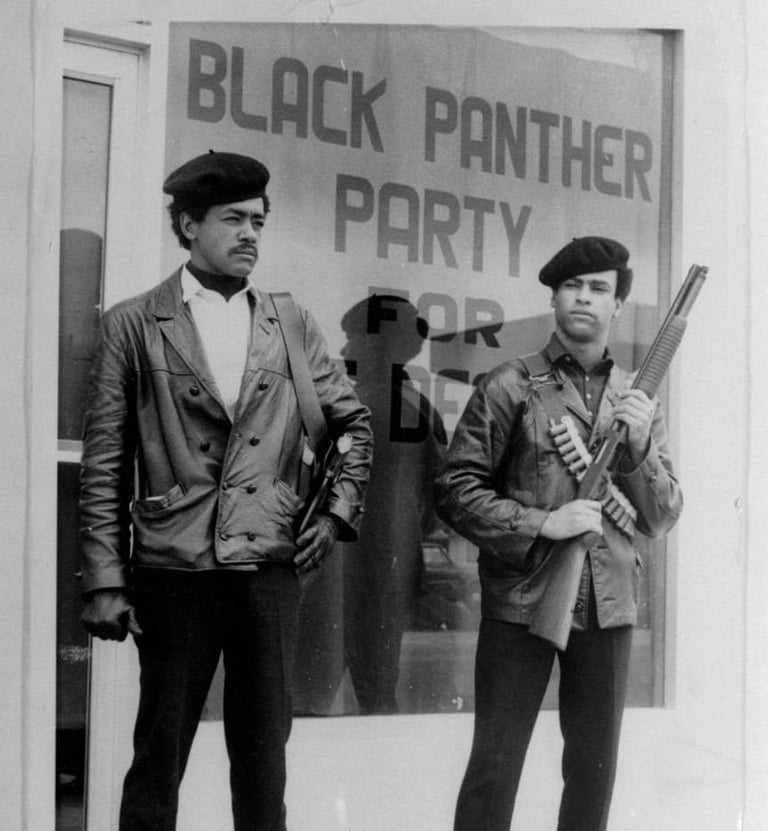

Black Panther Party armed demonstration at the California State Capitol on May 2, 1967.

The New Black Panther Party

The New Black Panther Party (NBPP) is a revolutionary organization that was founded in 1989 in Dallas, Texas, as a self-described continuation of the original Black Panther Party (BPP), which emerged in the late 1960s. Though inspired by the legacy of the BPP, the NBPP presents a different set of ideologies and strategies, often generating considerable controversy and public attention. The NBPP was founded by Aaron Michaels in Dallas, Texas where their main objective was cleaning up Black neighborhoods of drug dealers.

The 2nd Chairman of the NBPP was the Black Power General, Dr. khallid Abdul Muhammad . Khallid steered the NBPP towards a more Pan-Afrikan and Race first Ideology Inspired by The Nation of Islam's Fruit of Islam (FOI) and Marcus Garvey and the UNIA movement. As national chairman of the New Black Panther Party, khallid Muhammad would subsequently accelerate the armed self-defense movement like a national wildfire.

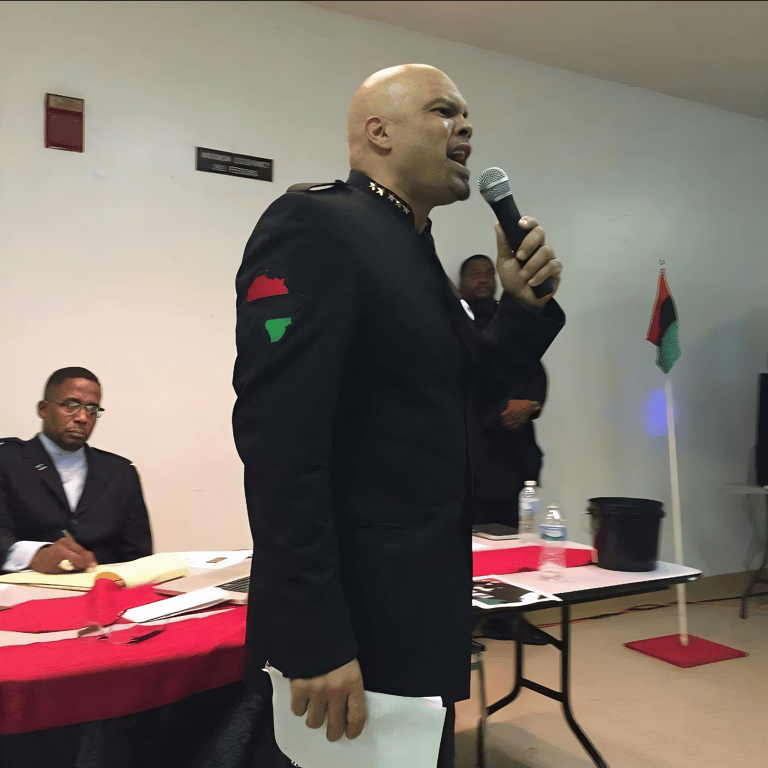

Malik Zulu Shabazz, served as The New Black Panther Party 3rd Chairman after the untimely death of Dr Khallid Abdul Muhammad. The group proclaimed its intention to fight for the rights of African Americans and promote self-determination. Its agenda included the advocacy for self-defense against police brutality, the establishment of community programs, and the call for reparations. The NBPP sought to increase its membership and visibility. The party participated in various demonstrations, often centered on police violence against African Americans and issues affecting black communities. The NBPP garnered significant media attention, especially during high-profile cases of alleged racial injustices, such as the police shooting of unarmed black men. The organization aimed to create a “political, economic, and social revolution” and often staged protests calling attention to systemic racism. Additionally, their rhetoric included the advocacy for the rights of black people not only in the United States but globally, reflecting a pan-African perspective. The simultaneously militant and community-focused approach characterized much of their activism. Controversies and Criticism Despite sharing a name with the original Black Panthers, the NBPP has been met with a mixed reception. In the late 2000s, the NBPP's notoriety increased notably due to its involvement in politically charged situations, most infamously during the 2008 presidential election and following the 2012 shooting of Trayvon Martin. The party's calls for “black self-defense” resonated with many, yet alarmed others, who viewed their expansion of militant rhetoric as potentially harmful. Also controversial was the group's stance on African-American interactions with law enforcement. These reactions were often responses to perceived systemic injustices faced by African-Americans but raised concerns among wider segments of the population regarding public safety and community relations. Influence and Legacy Despite the controversies, the NBPP has played a significant role in advocating for the rights and interests of the African American community. The organization posited numerous initiatives aimed at empowering black communities, which included youth programs, health initiatives, and educational campaigns. The NBPP’s visibility has waned and waxed, significantly influenced by contemporary movements such asthe Afro Descendant Movement. Successive generations of activists utilize social media and digital platforms to promote their causes, illuminating different aspects of the ongoing struggle for racial justice. Notably, while the newer group espouses many tenets of the original Black Panther Party, its direct legacy is more complex due to the varied interpretations and applications of black militant ideology in contemporary contexts. As social movements continue to evolve, the NBPP remains a powerful voice within the spectrum of advocacy for racial justice.

The next Chairman of the New Black Panther Party would be national chief of staff Hashim Nzinga, a well known Panther who prior to becoming Chairman regularly accompanied Dr. Khalid as he lectured and battled the overt racism Americanized Africans consistently encountered throughout the country. He soldiered at the NBPP’s Million Youth March in Harlem, Sept. 5, 1998, and the 2005 Millions More Movement in Washington, D.C.

Brother Hashim Nzinga at age 58, the National Chairman of the New Black Panther Party for Self Defense (NBPP), joined the ancestral realm Sept. 9, 2020, at his Atlanta home while surrounded by family and other loved ones, due to complications resulting from colon cancer.

The New Black Panther Party stands at a pivotal intersection of historical legacy and contemporary racial discourse. While it has echoed the cries for justice and equality that have been intrinsic to African American history, the organization embodies the complexities surrounding race, identity, and activism in the modern era. As America continues to grapple with its racial history and present inequities, the NBPP's contributions—however contentious—reflect the persistent fight for equity and justice among marginalized communities. The interplay between their activism and broader social movements illustrates a significant chapter in the ongoing narrative of race relations in the United States.

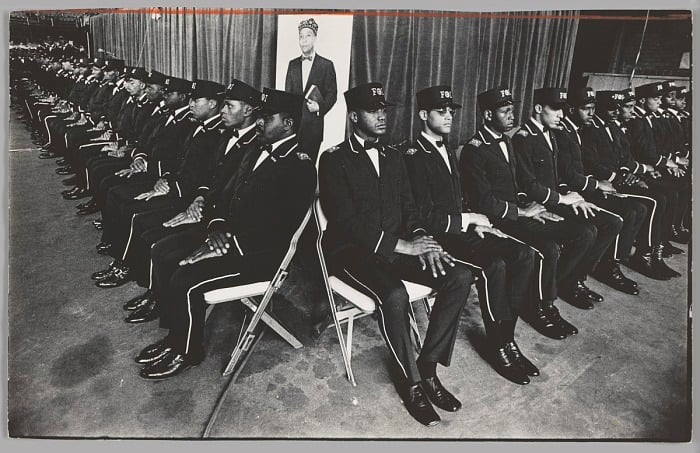

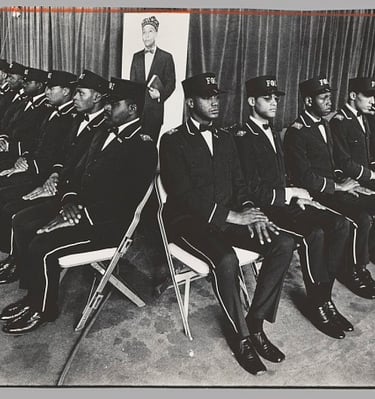

The Fruit of Islam (FOI) is the security and disciplinary wing of the Nation of Islam (NOI). It has also been described as its paramilitary wing.

Marcus Mosiah Garvey - Founded The Universal Negro Improvement Association, in Jamaica 1914

© 2024. All rights reserved.